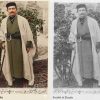

The Biography of Mohammad Bahmanbeigi

The Biography of Mohammad Bahmanbeigi

Mohammad Bahmanbeigi was born in a Qashqai tribe in a nomadic family in Fars Province, Iran, in 1921. When he was Eight years old, he learned the Persian alphabet through a clerk whom his father had employed. At the age of ten, the government sent first his father and then his mother to Tehran to exile. Therefore, Mohammad went to Tehran with his mother and studied at Tehran Seminary. After high school, he entered Tehran Law School and graduated in 1943. He went to the United States with the introduction of one of the Qaqaqi tribesmen and, after a short time, returned to his homeland.

learned the Persian alphabet through a clerk whom his father had employed. At the age of ten, the government sent first his father and then his mother to Tehran to exile. Therefore, Mohammad went to Tehran with his mother and studied at Tehran Seminary. After high school, he entered Tehran Law School and graduated in 1943. He went to the United States with the introduction of one of the Qaqaqi tribesmen and, after a short time, returned to his homeland.

For the first time, Shahid Modares, in opposition to the nomadic settlement policy, urged the government to establish a mobile school. However, this innovative thought was not considered in serious terms and little attention was paid to the training of the nomads. Several boarding schools were set up, but the schools were elementary and consequently the program made it inevitable for children from to live far away from their families in a condition like exile. This program was not sustainable.

Education and literacy in the Qashqai nomads has a challenging history, as far as Solat-al-Doleh Qashqai, once the President of the Qashqai tribes, made his best for the Qashqai children and youth to become literate in the 1920s. It should be noted that in 1952, the establishment of the first Iranian nomadic school was led by Dr. Mahmoud Hesabi (the Minister of Culture in Dr. Mossadegh’s cabinet). It was in the course of these activities that Bahmanbeigi set up his special educational tent in 1953. In this way, the first Iranian nomad teacher could teach tribesmen during the summer and the winter.

Education and literacy in the Qashqai nomads has a challenging history, as far as Solat-al-Doleh Qashqai, once the President of the Qashqai tribes, made his best for the Qashqai children and youth to become literate in the 1920s. It should be noted that in 1952, the establishment of the first Iranian nomadic school was led by Dr. Mahmoud Hesabi (the Minister of Culture in Dr. Mossadegh’s cabinet). It was in the course of these activities that Bahmanbeigi set up his special educational tent in 1953. In this way, the first Iranian nomad teacher could teach tribesmen during the summer and the winter.

A friend once told him that Americans could help him in fulfilling his dream of educating the nomads. Americans had already helped the government a lot with educational reforms and setting up schools in the villages. Bahmanbeigi’s friend had him visit the Principal of Truman’s 4th Trust in Fars Province, who, accompanied by Mr. Gigen, helped Bahmanbeingi speed up the process and succeed in his goals. 78 schools were ultimately established for Qashqai tribes, which were run by Bahmanbeigi and two supervisors, Bijan Bahadori and Nader Farhang Dareshoori.

However, since they were no educated and literate people in tribes, Bahmanbeigi and his companions had to invite teachers from cities to nomad regions by promising them to legally employ them and provide them with enough facilities. After a year, it became clear that these teachers could not live among the tribes and accompany them during their seasonal movements. In Bahmanbeigi’s words, “Once an urban youth was so terrified in a tribe that he saw a yellow dog in the form of a fox”. Bahmanbeigi found a way to find volunteers from tribesmen to educate them as teachesr, meanwhile paying them

One of the other strategies that developed Bahmanbeiqi’s work was to invite authorities and influential figures of the time to travel to his educational centers among the nomads. Dr. Karim Fatemi, the Director General of Education in Fars, along with a group of deputies from mobile schools paid visits to such centers, and their visit was enough to satisfy the Ministry of Education to agree to pay teachers’ salaries. Dr. Fatemi himself became one of the supporters of the program and called on Bahmanbeigi to employ teachers and continue to do so. After a while, tribal education developed beyond Fars Province to other parts of the country.

One of Bahmanbeigi’s innovative works that was beneficial in promoting his educational goals was organizing training camps for nomadic students and teachers in various tribal areas. In those camps, successful teachers introduced their own activities to other teachers and students. Performing local dancing and music were other programs in these camps, which proved very beneficial in preserving nomadic traditions and showing tribesmen that literacy and knowledge are compatible with local culture and can even develop it.